The history of Brouwerij 3 Fonteinen did not run in a straight line. Our story has curled and twisted more than the river Zenne itself. More than once, the future of the brewery was at stake, and more than once we needed steadfast minds and hearts to save tradition.

1882 - 1953 | In the mists of time.

For many lambic brewers and geuze blenders, their earliest history is shrouded in some mystery. Brouwerij 3 Fonteinen is no exception. The foundation goes back to at least 1882, when Jacobus Vanderlinden and his wife Joanna Brillens opened an inn in Beersel (at the location of today’s Hoogstraat 13).

The name 3 Fonteinen probably refers to the three porcelain hand pumps from which lambic, faro and kriek flowed, but that is not entirely certain. Recent research refers to the valley behind the brewery where three springs—then also called ‘fountains’—welled up. A third explanation is ancient mythology: many places take their name from three springs, such as the Tre Fontane abbey in Italy among others.

Jacobus and Joanna’s son Jan-Baptist, better known by the name of Tisjke Potter, continued the family business. From 1947 onwards, Tisjke got involved in local politics and even became mayor of Beersel in 1953. That is why, for lack of a successor in the family, he looked for a buyer for the inn called ‘In de 3 Fonteinen’.

1953 - 1982 | The rising popularity of ‘De 3 Fonteinen’.

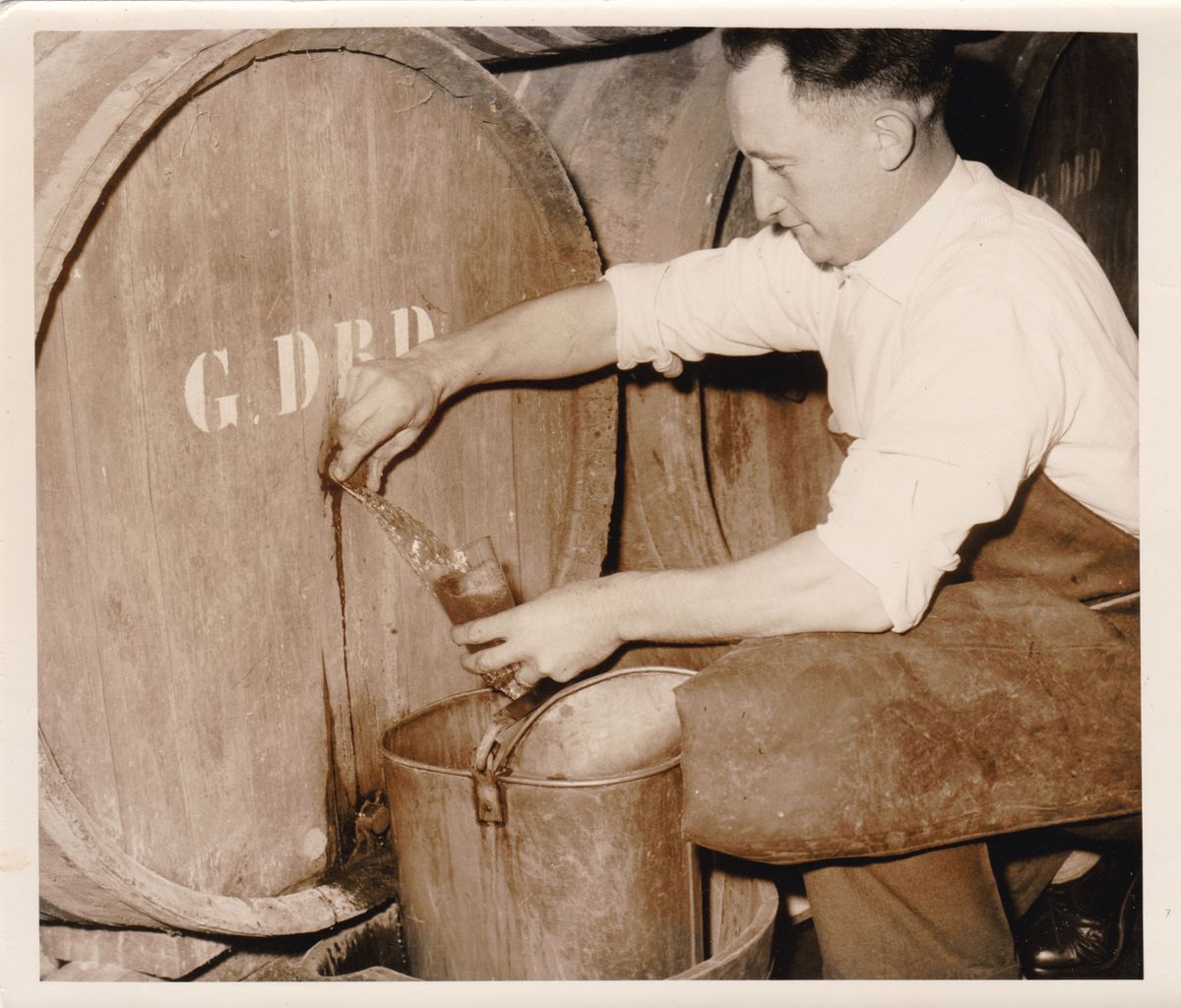

The year was 1953. After some initial doubts, Gaston Debelder and his wife Raymonde Dedoncker decided to take the big leap forward. They traded in their old farmer’s ways in the village of Elbeek for a new life in the centre of Beersel. The farm had become too small to support the entire Debelder clan, anyway. They took over the inn and geuze blending house from Tisjke Potter. And since the name ‘In de 3 Fonteinen' already hung on the façade, they just kept it.

Now, Gaston had to quickly master the noble craft of geuze blending. This may have seemed difficult for a man without any prior experience, who used to work on the land. However, the lambic microbes already ran through his veins, as his uncle Arthur Debelder had been a renowned blender in the 19th century. Besides, the transition from farmer to geuze blender was smaller in those days than it would be today. Both were artisans, intimately connected to what the local soil yielded and many farmers were still brewing themselves during the winter months.

The transition from farmer to geuze blender was smaller in those days than it would be today.

After nine years, in 1961, the Debelders bought an old building on the church square of Beersel. They tore the premises down to make way for a new pub- restaurant and the name 3 Fonteinen traveled along. Now, Gaston and Raymonde could start taking things to the next level. With a growing passion for the craft of blending, Gaston single-handedly dug caveaux under the new pub. These cellars were ideal to let the beer mature in all peace and quiet.

The pub rose to local fame in the ’60s and ’70s, with the so-called ‘Mijol Club’ as the epitome of its growing success. This club was founded by writer, artist and homo universalis Herman Teirlinck. He gathered an exclusive company of Flemish writers, artists, politicians and brilliant minds who were never shy of an opinion. People like Gerard Walschap, Maurice Roelants, Ernest Claes and Marc Galle spent hours in the pub while playing the ‘mijol box’, a folk game with small metal disks aimed towards a central hole.

Herman Teirlinck gathered an exclusive company of writers, artists, politicians and other brilliant minds who were never shy of an opinion. The beer itself was a topic of debate as well.

In between all the heated political discussions, the geuze flowed freely. The beverage itself was a topic of some debate as well, since Herman Teirlinck knew the history of regional beers inside out. We cannot overstate his influence on both Gaston and Armand Debelder—the latter still a toddler back then. The 3 Fonteinen pub continued to become the favourite haunt of many families from nearby Brussels, who flooded the village square on weekends to down a slice of bread with pottekeis (strong local cheese) with a geuze.

1982 - 1997 | Armand takes over.

After many years of success, Gaston and Raymonde handed over the business to their two sons. Armand, who had been behind the stove since he was sixteen, would run the kitchen and the geuze blendery. He became chef in 1974, at the age of 24. That is when he expanded the menu with regional dishes based on lambic, faro and geuze, because his true passion had always been beer rather than cooking. He had inherited his father’s nose, knowledge and experience.

During the ’80s and ’90s, the restaurant was a true magnet for the region. Everybody who was there still remembers the summer months when more than a thousand kilos of fries got baked in a week and when mussels simmered on the stove, ten kilos at a time. All the while, the geuze was still flowing as well. But the real challenge was now slowly raising its head... by the early 1990s, the consumption of geuze beer was at an all-time low.

Everybody remembers the summers when more than a thousand kilos of fries got baked in a week and when mussels simmered on the stove, ten kilos at a time.

The downward trend was due to a broader move, that had been going on for decades, towards cheap lager beers, sweet varieties of fruit beer and wine. Some even bluntly suggested to stop blending geuze altogether. The authentic way in which Armand performed his craft required not only plenty of time and patience, but money as well. The production and entire stock of geuze always had to be financed four years ahead, including the purchase of barrels. And after that, the bottled geuze still needed its time to mature.

In 1993, the Objectieve Bierproevers (Objective Beer Tasters) awarded their yearly trophy—for any deserving person in the world of Belgian brewing—to the only remaining authentic geuze blenders, being 3 Fonteinen, Hanssens and Moriau. This truly was the boost that Armand needed to know that he was doing the right thing. There still was a future for lambic and geuze. “Lambik, dat is bé van hé”: lambic is beer from here. And it is ours. Lambic beer is intertwined with our terroir, part of a local heritage that is too valuable to let it fade away.

1997 - 2009 | Armand Debelder stubbornly pursues as a brewer and blender.

It’s not easy to hang on to your belief in a future for lambic when even your father, who has witnessed the downward spiral of geuze consumption with his own eyes, openly declares you a fool. “Guis, da es allien nog voe d'aa peikes”, those were the exact words that Armand still hears his father saying. “Nobody cares about geuze except the old geezers.” Luckily, Armand had not only inherited his father’s nose but his stubbornness as well. Unrelentingly, he went all in on lambic and geuze, to start brewing himself in 1998.

Gaston Debelder, who has witnessed the downward spiral of geuze consumption with his own eyes, openly declares his son a fool. Luckily, Armand has also inherited his stubbornness.

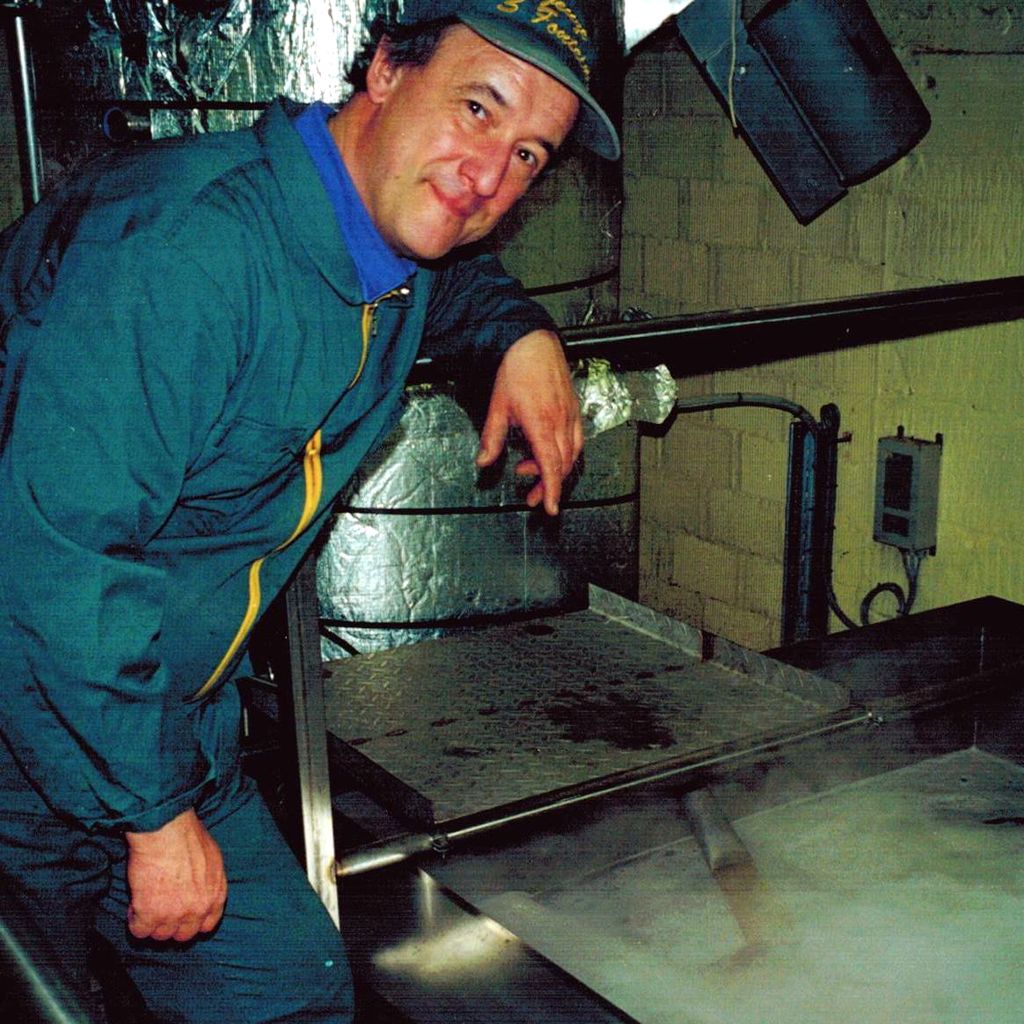

In a small brewhouse in the Hoogstraat (still in use today), the first wort flowed into the coolship in December 1998. The "brewery" 3 Fonteinen is a reality and later also becomes official with the founding by Armand of AD Bieren in 2001, which now continues as Brewery 3 Fonteinen. The local, regional, national and international interest in lambic and geuze beers surged as a part of local culture. Tourists from all over the world now drove around Brussels, the Zenne valley and the Pajottenland in search of that unique taste.

Meanwhile, Brouwerij 3 Fonteinen had steadily grown, and by 2008 the company was long-term financially stable. The yearly bottled production hovered around 800 hectolitres. This required a growing number of pipes, casks and foeders to buy and stow away. The wooden barrels now lay dispersed over four different locations, two of which were in Beersel and two in Essenbeek near Halle. Everything seemed to be going swell for Brouwerij 3 Fonteinen, if it hadn’t been for the night of 15 May 2009...

2009 - 2016 | The thermostat disaster and the recovery.

On Saturday morning, the 16th of May, 2009, Armand opens the door of the storage room. A heatwave literally blows him backwards. Fearing the worst, he storms into the warm room. This space, which was full of fermenting and conditioning bottles, normally stayed at a constant temperature of 18°C (64°F), kept in check by a thermostat. Due to a malfunction, though, temperatures had now risen to 60°C (140°F). At that moment, 13.000 bottles had already exploded from the rising pressure. The hall had turned into a war zone where Armand could still hear one bottle explode after the other.

Nailed to the ground in shock, the only thought he could muster was “We’re bankrupt”. The warm room contained a year’s supply in sellable stock, which also meant a yearly revenue. This is where Armand’s then fiancée entered the story. Together with a handful of enthusiasts, she helped Armand and the brewery to get back on their feet. Friendly brewers helped along by postponing due payments for 3 Fonteinen and there even was one American brewer who donated a part of the proceeds of a special brew. (source)

The hall had turned into a war zone where Armand still heard bottles explode, one after the other. Nailed to the ground in shock, the only thought he could muster was “We’re bankrupt”.

At the time, Armand was taking a course in distillery techniques and his teacher went along with a wacky idea: to distill the geuze. After a few tests, the experiment actually seemed to work. The beer had oxidized, but the aroma was still nicely in place and it delivered a tasty distillate. Two weekends after the disaster, a hundred or so volunteers helped to empty 65.000 bottles of geuze to serve as the basis for Armand’Spirit, a fine eau de vie with geuze character, distilled by the Distillerie de Biercée.

Armand also still had some of his own brewed lambic on oak barrels, which he intended to blend into future geuzes. A few American friends inspired him to turn those 3 Fonteinen brews into something special. The unique series of four blends would go down in history as the Armand’4 series: Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter. The geuzes were beautifully bottled and the sales exceeded his wildest dreams.

By 2011, Armand had sold his brewing installation and had injected a big part of his own private funds into the business. The support of friends, family and fans, coupled with the sale of Armand’Spirit and Armand’4: altogether, they generated just enough cash flow to make Brouwerij 3 Fonteinen barely survive. There was only one target now—to keep on going.

With his head barely above the water, but more motivated than ever, Armand sought the assistance of a new production assistant. In Michaël Blancquaert, then 26, he saw a younger version of himself: driven by the craft, inspired by tradition and eager to learn. Somebody with a fine nose as well, for whom only quality could be the criterium.

In Michaël, Armand saw a younger version of himself: driven by the craft, inspired by tradition and eager to learn. Somebody for whom only quality could be the criterium.

It wouldn’t be long before Armand and Mich expressed a mutual desire to start brewing again. In 2012 they set up a small brewing installation, custom-made for the well-known location in the Hoogstraat, with a coolship capacity of 3,000 litres. And so, they were launched again. But the spread of activities remained an issue. With no fewer than four different addresses, the transport of lambic and finished bottles between the different locations had become a logistical nightmare. Practicalities cost the company 200 man-days per year. The plan ripened to centralise all activities except for the brewing itself.

On a sunny Saturday morning in 2013, Michaël and Armand were talking to some insiders about their dreams for the future. That's when Werner Van Obberghen walked into the shop to buy his crate of geuze. Eleven years before, he had written his thesis on the problems of the small artisanal geuze blenders and he already knew Michaël from a brewing course. Although they were no strangers to each other, he felt honoured when Armand called him into the back room to explain his ideas.

Werner spontaneously proposed to voluntarily write a business plan for the next step. Armand had never been interested in numbers—except for the amount of litres in the barrels that he had to report for excise purposes. At that moment, Brouwerij 3 Fonteinen was still bleeding money, which it had been since the beginning of its existence, by the way. Every year, Armand put his own money into its operations. The challenge at hand: make a beautiful venture financially healthy, write and plan a future vision and convince the banks. In the end, the slowest of all beer crafts needed to be aligned with a financial perspective.

In the end, the slowest of all beer crafts needed to be aligned with a financial perspective. It was quite the challenge.

Michaël and Werner put all their subsequent Saturdays and Sundays into the effort. It is during these long sessions that the two became friends and laid the foundation for the succession that Armand Debelder had been dreaming of. When he saw them together, toiling away behind the laptop in the small kitchen in the back of the shop in Beersel, he casually dropped the words: “I like what I see happening now.” It was a phrase that would cling to Armand’s new associates forever.

In 2015, they finally found the perfect location in the Molenstraat in Lot. A large space, dry, with solid floors that were strong enough to support the lambic barrels and the entire stock of bottles. And just a few dozen metres from the Zenne. The dream of one place for all of Brouwerij 3 Fonteinen could now become a reality.

2016 - ... | New chapters. And an end.

Six thousand square metres. That is how much space they could suddenly use. Armand, Mich and Werner could not help but catch their breath when they first walked through the large halls of the old warehouse, but they realised that so much space also meant that they could take more time. The entire brewing process of 3 Fonteinen relies on slowness and patience: patience for the lambic in the barrel, for the macerating fruit, for the geuze in the bottle. And now, finally, there would be plenty of room for slowness. Or in the words of Armand: “Geft ne lambikbrààver of ne guizestèker plosj, en ze legge voete.” Give space to a lambic brewer or a geuze blender, and they roll the barrels in.

The barrel room, the bottling and labelling lines, the warm room and the administration: they could all come together now. Only the brewery itself would remain in the village centre of Beersel, because that location is at a higher elevation, which has a different nightly weather dynamic. However, it would be 2020 before the last barrel was moved and rolled into Lot. Filled barrels of lambic should not budge, so it took some years before they were all used and rinsed, ready for the next round.

Armand summed it up during one of his tours: “Our dad could just step in here today and continue to do his thing.”

From then on, the capacity of the barrel room grew steadily, keeping one golden rule in mind: maintain a good balance of young and old lambics. Visitors may be impressed by so many oak barrels, but the process has not changed. Armand summed it up during one of his tours: “Our dad could just step in here today and continue to do his thing.”

A vast variety of dozens of landraces wheat and barley. A manual brewing process. A completely natural cooling on the coolship. A full spontaneous fermentation and paturation on oak barrels and foudres. Never on draft, always on bottle. No artificial additions. Such a 100% natural process is certainly not the standard in today’s lambic world. But respect for tradition does not mean there is no room for experiments. Quite on the contrary. Between 2015 and 2020, the team grew to twenty people, and together they blew a breath of fresh air into the Zenne Valley.

More old wine and sherry barrels were brought in, together with new varieties of fruit, for trials in the brewery and experiments in the barrel. They all appeared under the heading ‘Speling van het Lot’ (Twist of Fate). The premise was simple: keep trying. If the result was good, it would be sold, otherwise it wouldn’t be. Armand’s beloved lambik-O-droom was also revived: a meeting place and tasting room, attracting both the locals and the international beer aficionados.

The concept of ‘terroir’ stands for the involvement of fruit growers, farmers, artisans, enthusiasts and even neighbours.

The ambition, meanwhile, extended beyond the walls of the brewery. 3 Fonteinen wanted to help bring our terroir back to life. How? By involving fruit growers, farmers, artisans, enthusiasts and even the neighbours. Because together, they are intertwined in one story, one tradition, one culture.

The first example of the organised approach started with an —almost accidental— call for Schaarbeekse sour cherries. These small cherries have little commercial value in the supermarket, but are the best for a typical Kriek. The response was overwhelming: in addition to a few families that already brought in their harvest, some twenty new families suddenly came over. By now, the count has already reached over one hundred. The Centre for Botanical Enrichment, which specialises in old fruit species, is now also helping with a multiplying programme, in the hope of reaching over 2,000 trees in about ten years, allowing to only use local sour cherries. By then, also all other fruit is sourced directly with organic fruit farmers.

Other collaborations ran along the same line: with a potter (for the lambic jugs), with a basket weaver (for the willow baskets), with a glassblower (for real geuze glasses like back in the day) and with an enamel company (for the traditional enamel beer signs).

But the pièce de résistance would be the cereals. Our old barley and wheat varieties have been entirely supplanted by industrial agriculture, and it would take a whole network of organic farmers and committed buyers to do something about that. The Cereal Collective is now up and running, added with some hops as well, fully fulfilling an old wish of Armand.

Only fate still tried to throw a spanner in the works. In the spring of 2019, a good two years after Armand's retirement, terrible news hit him out of the blue. His doctor told him he had metastasised cancer. With heavy medical treatment ahead, he decided to dispose of his stake in the brewery, “so as not to jeopardise the future of 3 Fonteinen, should something happen to me tomorrow.”

Despite the relentless desire to fight for it, he ended up in hospital in the summer of 2019, completely physically exhausted. From then on, Opa Geuze, as the children of the team called him, would spend less time at the brewery than he would have liked. The corona pandemic in the spring of 2020 made things even more difficult. Still, every opportunity was valid for Armand to make his rounds in Lot.

Until he couldn’t anymore. On Sunday 6 March 2022, just after midnight, Armand Debelder passed away. Pater familias of the brewery and blendery, and a second father to his successors.

With heart and soul, Armand determined the course of 3 Fonteinen, all his life. And in the last few years he had helped to set out and to draw the lines of the long future. For the beer of course, but also for the spirit, the values and the character. Will new chapters still be written for Brouwerij 3 Fonteinen’s story? Definitely. And that story will always belong to Armand.