De Kleine Rosse van Brabant, literal translation: the Little Redhead from Brabant. Right up to the 1970s, this beauty was waving on fields in the Pajottenland region, but today she has disappeared along with all other local landraces. And yet, the redhead among the wheat varieties had been part and parcel of local lambic culture for ages. Our dream today is to start growing and using these old varieties again.

To begin with: how exactly did we lose those landraces? Long story. Whoever still cherishes the romantic idea that every farmer works the land with gnarled hands, ploughing through the mud in rubber boots... think again. “Today, farmers have increasingly become managers,” says Lucas Van den Abeele, who helped build the local cereal collective in and around the Pajottenland. “All too often, they have no direct connection with the soil they’re harvesting from. In the better case, they still see the land from their tractors, but they might just as well be filling out Excel sheets on a laptop. They’re producing for the global market and don’t know where their crops are going.”

Will the cereals serve for beer or bread, animal feed, the starch industry or biofuel? No idea. Will they stay in Belgium or travel to Poland or Kazakhstan? No idea. Of course, things were different in the days of yore. But for that, we need to turn the clock backwards for half a century.

More proceeds with less manpower.

Up until World War II, the majority of our population still had a connection with agriculture. If you weren’t a farmer yourself, then you probably had one in the family. And if it wasn’t in your generation, then it must have been your grandparents. “There was a real connection with the land,” Lucas explains. “People just knew that you couldn’t have strawberries on Christmas. That’s different now, because every kind of fruit is gleaming bright and shiny in any supermarket, any time of year.”

The war then brought Europe to its knees. Once it blew over, the feeling arose on the continent that we needed to modernise, do things like the Americans did. In France, the manpower available for agriculture had been halved, because so many farmers’ sons had perished on the battlefield. At the same time, factories were luring labour away with the (quite real) promise of better wages. “The farmer’s business was collapsing. Just to get enough cereal here to feed all these mouths, we depended on import from both the Soviet Union and the United States. That made our governments feel itchy. Not only did we battle a deficit, we also had to deal with an inferiority complex.”

Sicco Mansholt, the first European Commissioner for Agriculture, was a Dutchman who had lived through the great winter famine and had experienced those miserable food stamps first-hand. It was with the best of intentions—“No more famine!”—that he started promoting industrialisation and large-scale economies. To him, the concepts of ‘successful’ and ‘more’ were synonymous. Fields had to yield more, more, more, and the mantra “Get big or get out” wasn’t used ironically in the first European Agricultural Policy of 1958.

Mansholt, who by the way had been a farmer himself in the area of Groningen, did, however, cherish the conviction that every peasant deserved a proper income. “Unfortunately,” Lucas adds, “that's where his policy failed. A farmer's income never transcended that of an unschooled factory worker. In a factory, all labourers also worked with fixed hours and they were rewarded with days of leave, whereas in agriculture everybody expected a farmer to be available non-stop, working day and night if need be.”

Farmers and cereals walk in line.

Up to this day, we feel the consequences. The European funding that farmers get now actually supports the agro-industry. Farmers receive extra money so they can go on selling their cereals under the market price. Instead of customers, an agricultural worker only sees technical consultants who tell him what to buy and when it’s best to invest, with the sole aim of keeping the tax authorities happy. The advice comes from the same people who also sell the machinery and the sowing seed and who indirectly also manage the loans.

“They advise, but actually, they're selling,” Lucas confirms. “The situation is absurd and suffocating. Farmers are no longer players in this game, they are being played by higher powers. We call it one of the lock-ins of the current farmer's life. There is no easy way out of this situation because everything is so connected.”

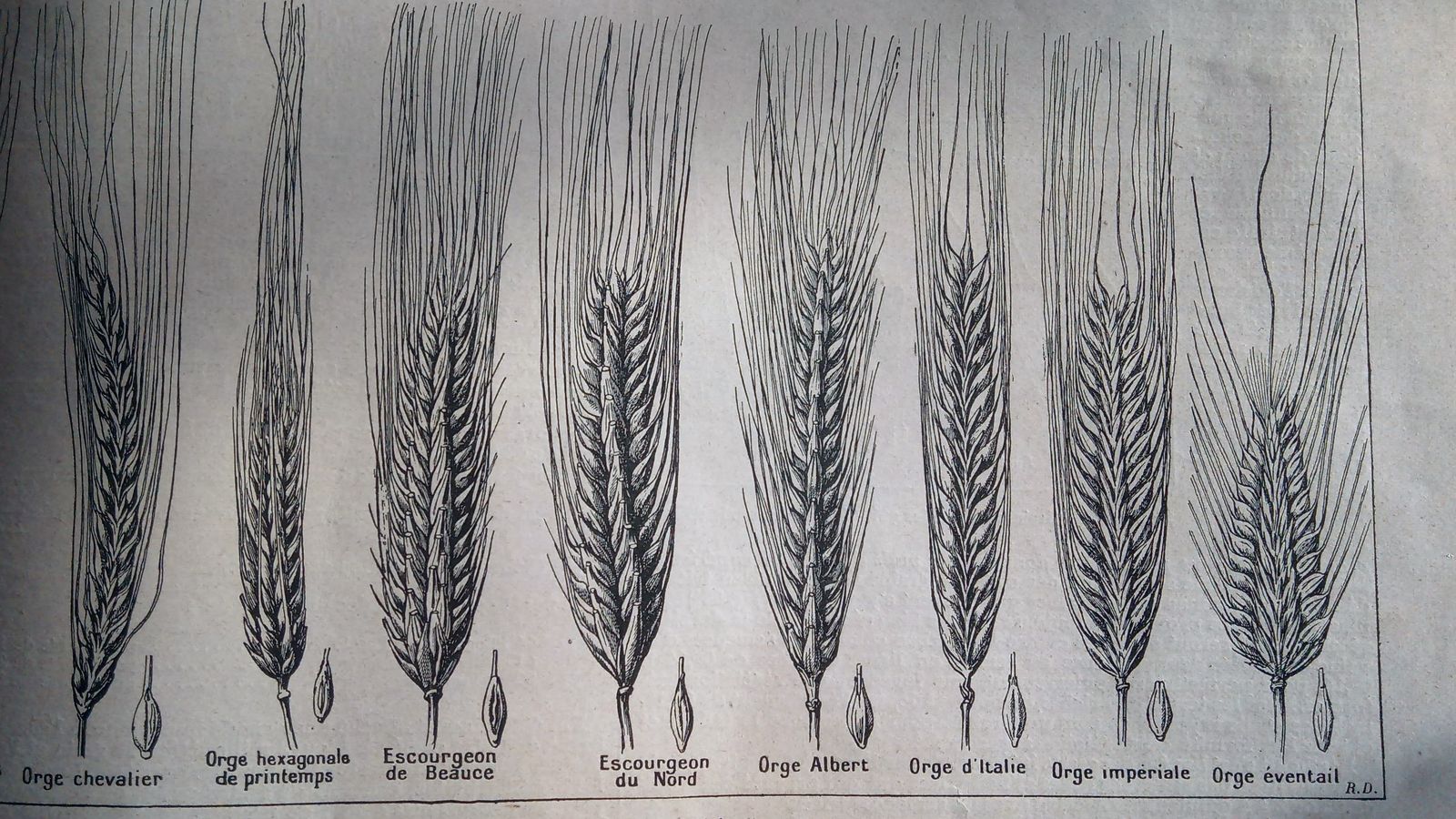

Modern wheat and barley races are what we call ‘pure line races'. That sounds good, but actually, homogenisation has all but destroyed the natural flow.

And it's not just farmers who have to walk in line. Nature itself has also been shackled by industrial agriculture. For decades now, everything has been dominated by standardisation. Modern wheat and barley races are what we call ‘pure line races'. That sounds good, but actually, homogenisation has all but destroyed the natural flow. It’s one of the fundamental issues that agroecologists want to tackle.

Agroecology is the science that looks at how our food system is, in fact, an ecosystem in itself. Farmers, processors and consumers all influence each other. When things go wrong on the field, the farmers will suffer, and vice versa. Without political interference, nothing will change the status quo of agricultural lock-ins. This is why agroecology is not only a science, but a social movement and daily practise as well.

Marjolein Visser teaches agroecology at the ULB University in Brussels. She was Lucas's promotor when he was researching his thesis. “When you want to add a race of cereals to the European registry,” Marjolein explains, “it has to meet three criteria: Distinctness, Uniformity and Stability. However, the U in the notorious DUS-criteria has increasingly come to stand for genetic uniformity. It's a complicated story, but what it boils down to is that processors of beer, bread or animal feed expect to receive the exact same product every year, with the exact same protein level up to the final comma. It's the only way they can standardise their product for the global market. This leaves no room for variety whatsoever.”

“However, that’s not how nature works,” she adds. “The circle of life benefits from subtle differences in genetic material.” When disease or pests strike, some plants will coincidentally turn out to be resistant and will then assure the future of that variety. It’s a very haphazard thing. But the chemical industry does not like this game of chance.

“For them, it’s not interesting to have plant races that are naturally protected, because then they will sell fewer pesticides. Look, all modern cereal races are sprinters. The old landraces were long-distance runners: they yielded less but lasted longer. Take climate change for instance. If you would let nature have its way, it would find a way to cope with rising temperatures and modified soils. A genetically diverse race is creative enough to work around the changing circumstances.”

In the old days, a farmer used a part of his harvest as sowing seed for the next year and he also exchanged it with colleagues, which only served natural variety. Today, a farmer is allowed to reuse his sowing seeds, but he can never sell them. Even worse are the F1 hybrid seeds, the ultimate accomplishment of the agro-industry. Those are seeds with a ‘non-stable genetic uniformity’.

Professor Visser clarifies as follows. “When you sow the F1 hybrids, they will yield a perfect harvest once. However, if you use seeds from the first harvest for the next season, the return will plummet. Every seed that you put into the ground again will behave erratically and degrade the crops right away.” This is nothing less than self-destructive nature. The process makes sure that a farmer needs to pass by the cash register over at global agro-industrial corporations, year after year after year.

The holy grail of wheat grains.

Needless to say, this system does not leave room for our Little Redhead from Brabant. The old local wheat race has been replaced by other varieties without anybody taking note—except for a few dreamers. Armand De Belder knew very well that the old landraces used for traditional lambic had disappeared. It was not a thing he could easily solve, because by then, farmers and brewers had already grown apart. This changed in 2018.

Tijs Boelens (a local Pajottenland farmer), the millers of the old Flietermolen (a mill in Tollembeek), Lucas Van den Abeele (then still a student) and Brouwerij 3 Fonteinen joined forces to create the cereal collective. Their aim? To re-establish contact between farmers, bakers and brewers in a regional network. On a small scale, they wanted to break the chains of industrial agriculture, to gradually restore the old landraces and, very importantly, to strengthen the bonds between all players in the cereal chain. One year later, ten farmers had already joined.

Everybody praises geuze as the finest regional produce, so isn't it plain logic that the cereals should also come from around here?

In the meantime, Lucas has been searching for the landraces in seed banks all over the world. Many seeds have sat frozen there for decades, like on the Norwegian island of Spitsbergen. There, a thick layer of permafrost protects the grains for eternity. So far, Lucas hasn’t retrieved the Holy Grail of the Little Redhead, but he did find eleven old races from the same region in an American seed bank.

Of these eleven varieties, he ordered five grams each, which is less than a handful. He planted every seed manually on a small field managed by Tijs Boelens in the village of Pepingen. In turn, Tijs cultivated them with the best of care, so that the first harvest yielded one kilogram already. Etcetera. After five years, this should lead to the first 300 kilos of wheat, enough to fill a barrel of lambic.

Farmers in the cereal collective receive a fair price for their grains and they are now exceptionally aware of the aim they will serve: tasty lambic beer. The target now is to experiment, to find a race that performs as well on the field as in the barrel. Everybody praises geuze as the finest regional produce, so isn't it plain logic that the cereals should also come from around here? Everybody in the collective firmly believes that, if and when the story works out, the beer can only taste better in turn.

Networking does not happen on Facebook.

Meanwhile, there are twelve farmers in Brabant in the cereal collective, all within 25 kilometres of the brewery. That is not a strict limit, as long as participants can get directly in touch. Perhaps we should call it ‘within tractor distance’. Anyhow, this will sort itself out. There are two other vital rules in the game, though.

Firstly, for the beer we only use organic grains. Secondly, all partners need to work together. That sounds a bit soft around the edges, but it’s a stone-cold truth. Farmers need resilience for when fate strikes. Adversity can always arrive in the shape of a price crisis, water shortage or a sudden bereavement, and that’s when a strong social network can make the difference.

The partners need to work together. That sounds a bit soft around the edges, but it’s a stone-cold truth. Farmers need resilience for when fate strikes.

“It's about people who know each other. The informal aspect truly counts,” Lucas stresses. “I have dragged my colleagues at 3 Fonteinen out to visit the fields, I have invited the farmers to the brewery and I have tried to establish more contact among farmers themselves. My job is unique because nobody else sees this benefit of cooperation. And if they did, they would not be willing to pay for it. That’s why so many other projects fizzle out once the research phase is over or once the funding dries up. Here at Brouwerij 3 Fonteinen, we see things differently.”

Once upon a time, farmers became brewers themselves in wintertime, when there was less work on the field. They used a part of the harvest for their own beer, that could then be drunk on the field in the next season. Are those days of yore coming back? Who knows. But soon, at least some brewers and farmers will be able to uncork a bottle of geuze that they have truly filled together.